I always knock on wood and consider myself lucky when I’ve escaped some of the pitfalls of chicken keeping. But in the last few months I seem to have been hit with a few issues: my first raccoon fatality, my first mink in the pen (no damage), a hen with a recurring prolapse and several assisted hatches.

I donated eggs to a couple of elementary schools and got the chicks back just over a week ago: I’ve been preoccupied doing physiotherapy with one who developed a slipped tendon (not sure when) and didn’t notice anything amiss with her hatch mates. When I went to check the brooder three days ago,I found a dead chick, who had seemed perfectly fine the day before. Most of the others were okay, but one of the bigger cockerels was fluffed upped and hunched in their crate. Not a good sign. Then I saw a dark spot on the shavings and when I touched it discovered wet blood: the telltale sign of coccidiosis. Again, a first for me.

Coccidiosis is an intestinal disease caused by a microscopic parasitic protozoa, which attaches itself to the intestinal lining of a chicken. There are six different species, some harmless and others life threatening, each living in a specific area of the gut. They damage the tissue causing bleeding (hence the bloody poop) and prevent birds from absorbing nutrients. Chickens of all ages can become infected but most vulnerable are chicks under six months because they haven’t built immunity against it.

I don’t have an incubator but I do have plenty of broody hens. The advantage of hens is they are out in the pen, scratching in the soil with their just hatched chicks, exposing them to small amounts of pathogens, which build their immune systems gradually.

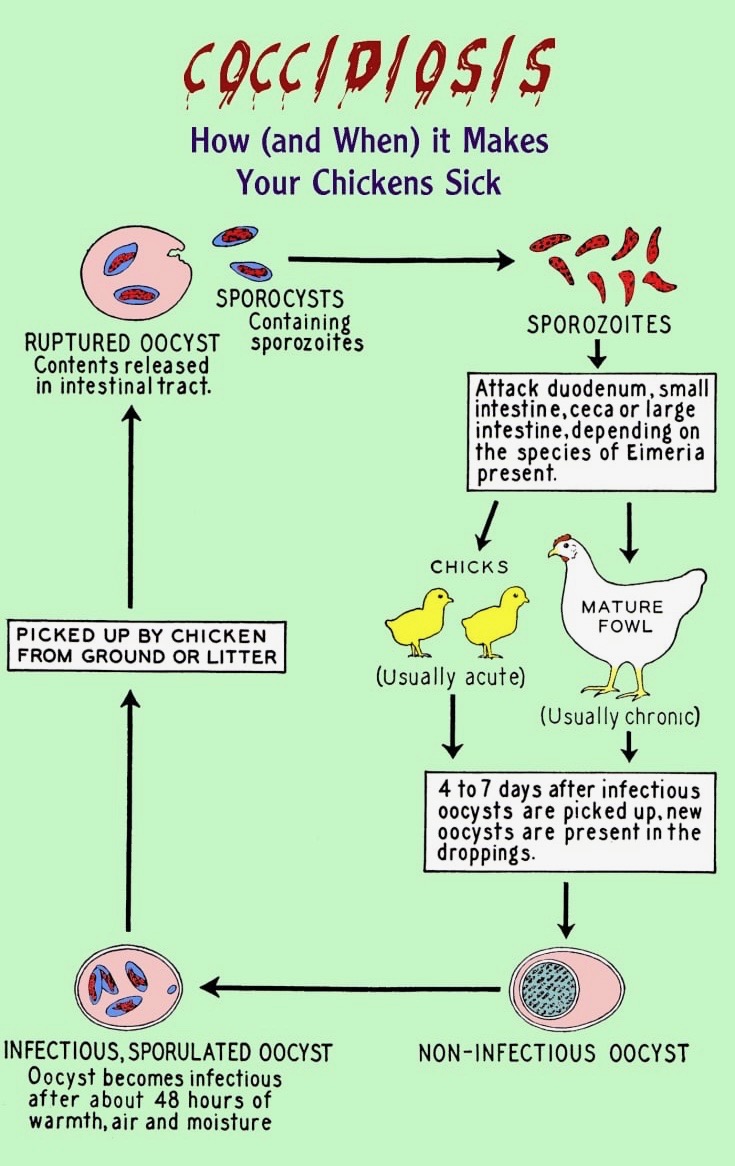

Most chickens carry the coccidia organism in their bowel but only some will develop the disease, which starts as an egg passed through chicken poop. An oocyst (egg) can lay dormant in the soil for up to a year (unless killed by freezing) and isn’t infectious until it sits for a few days in wet or humid conditions (e.g. around feeders and waterers).

When a chicken eats an oocyst, either through contaminated water, food or when it scratches in the earth, digestive chemicals break down the hard layer protecting the oocyst enabling it to invade the cell lining in the small intestine. The parasite goes through several life stages, multiplying inside the chicken and at each stage rupturing more cells within the bowel, resulting in ulceration.

A single oocyst can destroy thousands of gut cells. If a chicken consumes only a few oocysts they won’t get sick and will be immune to coccidiosis. If birds ingest large numbers, potentially millions of cells are killed. It is a painful condition, which causes birds to stop eating and to appear hunched with ruffled feathers. The damage in the gut reduces an affected bird’s ability to absorb nutrients resulting in weight loss and diarrhea. In severe cases damage creates bleeding in the gut, which gets passed out in poop. They may develop anemia characterized by pale wattles and comb.

The coccidia oocyst will be expelled in the chicken’s poop and can then go on to cause infection in your other birds if they eat it.

So how did my chicks get infected?

Incubator chicks require heat lamps and even in warmer weather, aren’t outside until they are several weeks old. That puts them at risk for parasitic infections like coccidiosis, because once out of a sterile brooder they have zero immunity.

When I first brought them home they were in a plastic brooder that had been thoroughly cleaned. Once they got a bit bigger they were housed in a nursery area within my coop. I cleaned it, but it’s impossible to remove all traces of fecal matter and there must have been residual amounts of poop from other birds there.

Temperatures of 25-30c are ideal breeding grounds for coccidiosis. That’s just the temperature of my three-week old chicks’ new space – again, the perfect conditions for an outbreak. I cleaned their waterer and feeder daily but chicks are messy. They splashed water in the shavings and on the floor. The moisture and temperature allowed the oocysts to become infectious and then the chicks ingested them.

Chicks can become symptomatic quite quickly. One day they were fine, and by the following day, one had died and another looked off. The others looked totally healthy. Not all birds will consume the same number of oocysts or have the same symptoms. It’s now clear that my flock has been exposed to coccidiosis, but I have never had a bird be symptomatic.

What To Look For

- Bloody poop

- Watery, loose poop

- Decreased appetite

- Lethargy, sleepy

- Huddled together, appear cold

- Failure to thrive

- Weight loss or decreased egg production in adult birds

Treatment

Amprolium (Corid) is a thiamine (B1 vitamin) blocker, which prevents the oocysts from reproducing. It allows some oocysts to remain in their system triggering antibodies to build immunity against the disease. It comes in liquid or powdered versions – I used the latter. Recommended dosage depends on the severity of the outbreak. There is no egg or meat withdrawal period.

This was the only chick that appeared sick – hunched, sleepy and fluffed up feathers – so I brought him into the house on the first night to give him the meds via eye dropper. Since one of the symptoms is decreased appetite I was concerned he wouldn’t drink enough water to absorb the Amprolium fast enough. He turned out to be a co-operative patient and consumed several eye-droppers filled with water and Amprolium solution so I returned him to his hatch-mates. After 48 hours there was no more evidence of bloody poop and he is on the road to recovery.

Prevention

Like most disease prevention, coccidiosis is all about bio-security and hygiene. The parasite can be introduced into your flock by wild birds, new chickens or on your shoes and clothing. Be careful about where you’ve been (i.e. places with chickens) and cross- contamination.

Clean you coop often – don’t let poop accumulate.

Ensure that your coop is well ventilated and not overcrowded.

Quarantine new birds for at least three weeks in a separate area.

If you are giving your chicks medicated feed it contains Amprolium and is designed to reduce their chances of becoming infected for the duration they are consuming it. It will allow them to build up their immunity if they ingest small numbers of oocysts. It will not protect them once they are no longer eating it.

Hatcheries often vaccinate day old chicks for coccidiosis – check whether your birds have been vaccinated. If so, do not feed them medicated starter crumbles as the Amprolium in it negates the shots.

Most chickens, especially small flock birds that are often not vaccinated and are exposed to outdoor environments, have been exposed to coccidiosis at some point. If your birds are healthy they often develop antibodies and never become symptomatic. I’m hoping all my chicks, once treated, will rebound and become immune to it in the future. To assist them I’ll be giving them poultry vitamins once they’re finished their regime.

This is another lesson about how things can change on a dime. With chickens you always need to be working on prevention and being vigilant for any changes in your birds. Sometimes just a few hours and a small intervention can avert potential disaster.

As usual, your information is to the point and so helpful! Thank you! Crossed fingers that my chicks build immunities quickly!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much for your easy to understand instruction on this invaluable information! I love your site and feel like I’m always learning something new!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for your incredibly interesting and useful information. Have just ordered some Corid from the states, can’t seem to find it in Canada.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I wish I’d known sooner – I have some I could have passed on to you.

LikeLike

Excellent article

LikeLike