When you look at a flock of chickens, one of the first things you might notice is their combs – those red, fleshy bits on top of their heads that come in all kinds of shapes and sizes. From the tidy single comb of a Leghorn to the wild rose comb of a Wyandotte, combs are more than fashion statements – they’re genetic signatures.

There are nine distinct types of combs and then a bunch more of what are called duplex or combination combs – all which have evolved from the original rose and pea combs. So what is the purpose of those protrusions on the top of their heads that some folks refer to as cones or crowns?

The comb is made up of bundles of collagen fibres in the form of protein bundles, similar to a bungee cord, helping to give the comb its elasticity. It’s an organ consisting of a network of arteries, veins, and capillaries that form a mini-circulation system that allow for rapid heat exchange between the blood vessels. Blood is pumped into the comb and temporarily held there through a network of shunts that open and close when needed. The network of blood vessels helps to maintain its body temperature during the heat of summer and the cold of winter. Combs are also a means of advertising a both health and sexual status.

The Basics of Comb Genetics

Comb type in chickens is determined by a small number of major genes that interact in predictable ways.

The two key genes that determine most comb shapes are:

- R (Rose comb gene)

- P (Pea comb gene)

Each of these has a dominant and recessive allele:

- R = rose comb, r = single comb

- P = pea comb, p = single comb

The single comb, seen in most Mediterranean breeds like the Leghorn, is the recessive form. It appears only when both genes are in their recessive state (rr pp).

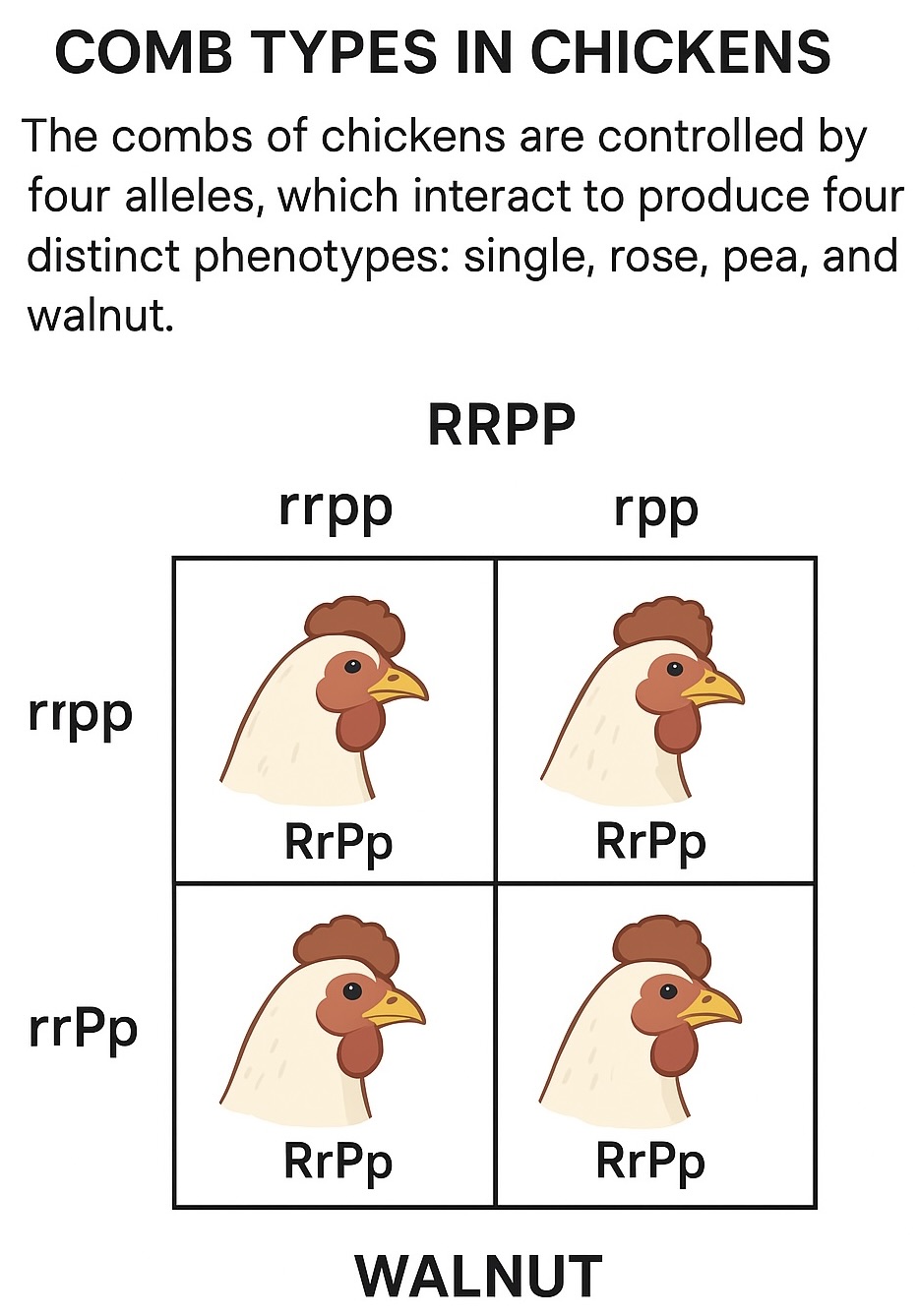

Combs are controlled by four alleles, which interact to produce four distinct phenotypes: single, rose, pea, and walnut.

You can use mathematically probability to predict crosses that involve multiple traits. Punnet squares become unwieldy when multiple alleles are involved. Many can be solved visually, without using math or a Punnet square. For example, the cross rrpp x RRPP will always produce chickens with the genotype RrPp, which will result in walnut combs.

Classic Comb Types and Their Genotypes

Here’s how some of the most common comb types work genetically:

Single Comb (rr pp)

- The simplest form, with a straight ridge and evenly spaced points

- Common in Leghorns, Australorps, and Rhode Island Reds

Rose Comb (R_ pp)

- Caused by the dominant R allele

- Broad and flat, often ending in a spike

- Seen in Wyandottes and Dominiques

Pea Comb (rr P_)

- Caused by the dominant P allele

- Short and bumpy, divided into three small ridges

- Found in Brahmas and Ameraucanas

Walnut Comb (R_ P_)

- When both dominant alleles are present together, the result is a walnut comb, a rounded, bumpy mass

- Typical of Silkies

- This is a classic case of gene interaction or epistasis, where the effect of one gene is modified by another

Other Variations and Modifiers

- Beyond the R and P genes, modifier genes can tweak size, thickness, or shape

- The cushion comb and buttercup comb involve additional genes, making them less predictable in inheritance

- Comb size is also influenced by sex hormones; larger in roosters due to testosterone.

Why Comb Genetics Matter

- Combs aren’t just decorative. They play a role in thermoregulation, helping chickens release excess body heat.

- Certain comb types may have evolved for specific climates: small pea or rose combs resist frostbite better than tall single combs.

- In breeding, comb genes are used as genetic markers, since they follow clear Mendelian inheritance and are linked to other traits, like fertility or egg production.

- One study demonstrated there is a relationship between comb size and colour with sperm quality and viability. It turns out that colour is paramount and bigger is not better. The roosters with the smallest, reddest combs had the highest percentage of viable sperm.

Fun Fact: Comb Genes and Chromosomes

- The rose comb gene (R) is located on chromosome 7, while the pea comb gene (P) sits on chromosome 1.

- The walnut comb’s distinct texture results from epistatic interaction – when the expression of one gene modifies or masks another’s effect.

The Takeaway

That little red ridge on your chicken’s head is more than decoration – it’s a visible expression of genetic coding. Whether your birds sport rose, pea, or walnut crowns, their combs are living lessons in Mendelian genetics, selective breeding, and evolutionary adaptation.

Citations:

- Dorshorst, B., Okimoto, R., & Ashwell, C. (2010). “Genetic mapping of the rose comb and pea comb loci in chickens.” BMC Genomics, 11(1), 18.

- Somes, R. G. Jr. (1990). “Mutations and major variants of plumage and skin in chickens.” Poultry Science Review, 2, 121–143.

- Warren, D. C. (1923). “The inheritance of comb forms in poultry.” Journal of Heredity, 14(2), 57–69.

- Fleming, D. S., et al. (2016). “Genomic analysis of chicken comb morphology reveals epistatic interactions.” Genetics Selection Evolution, 48(1), 77.

“Bringing science to the coop — one experiment at a time.”

0 comments on “The Genetics of Chicken Combs: What Those Crowns Reveal”