For those of you who don’t know, I live on a small island off the west coast of Canada (pop. 4500).

Imagine my surprise when I picked up a copy of last week’s local paper. First of all, the headline featured chickens, but more importantly why wasn’t I invited to that auspicious event?! Not to be left out I contacted their owner, to ask if I could interview her and the now famous hens, about their attempt to get into the Guinness Book Of Records.

Emily, or should I say Dr Carrington (she’s a small animal veterinarian with no avian experience) invited me over to show off her birds and offer some insights into the workings of the chicken brain.

“I got a group of six of them a few years ago for my father who was quite elderly and I thought it would give him something fun to do. He really enjoyed them. Collecting the eggs was his last ‘job’ and I think it really gave him a sense of purpose. The chickens loved him too and would pace excitedly in their pen in anticipation when they saw him putting on his coat and hat through the living room window to go and see them and give them some scratch.”

Her initial goal was to investigate how they learn, but as it turns out she’s learned a few things about her feathered friends along the way. As an inexperienced trainer it took her awhile to figure out how chickens acquire knowledge and what their limitations are. She did some internet searches on research studies, of which there is little and mostly limited to imprinting day-old chicks, and decided her science background could add to the body of knowledge about chicken cognition. Her methods involved a bit of trial and error, which she has streamlined along the way.

Emily’s small flock keeping practice is somewhat unusual: not only does she adhere to an all in-all out flock management to avoid biosecurity issues of adding and rehoming birds along the way, but she takes a year or so off between flocks. During her hiatus she catches up her busy schedule: working part-time as a vet in another community, writing her second graphic novel, painting, gardening and maintaining the house she built.

She got her first trainees a few years ago and “kept them for a year and then let them go to a nice little farm with much more room to roam than I have. They seemed to really like it there and I thought I would do the same with this group.”

When Emily first went to visit them they recognized and came to greet her. Interestingly, within a week or so, after having been introduced to a rooster for the first time, their focus shifted to him and they had seemingly lost interest in their former keeper. I wondered if training hens that are not housed with a rooster might be easier in that the flock hierarchy is different.

“I am not sure. I live on quite a small lot and I think a rooster would be too noisy for both me and my neighbours so I don’t think I will get one. The hens are so motivated to learn things for treats though that I am fairly sure they would still be trainable if I just worked with them one at a time.”

Her current flock consists of six Hyline hens purchased at four months old. They’d never been handled but quickly adapted to not only being picked up but working with a trainer. One of the hens, who suffers from a reproductive tract issue and has stopped laying, missed the initial classes during her treatment and recuperation, but the other five are all stellar pupils.

I’ve never attempted to train my chickens, not knowing where to start but also perhaps believing that they weren’t capable of learning multiple commands and tasks. I’ve had three Standard Poodles, all who lived up to their reputation of being in the top five smartest breeds and had a fairly wide vocabulary. For instance, when I asked them to fetch a toy they could differentiate between stick, ball, stuffie, bone, etc.

Emily’s not sure if chickens understand human language or not, but they do respond to physical cues, colours and shapes. That makes sense because birds, even flightless ones like chickens, have a territory which they constantly map in order to find food and shelter and avoid predators.

My partner and I live on 4½ acres surrounded by forest that is home to many species of birds and even a few reptiles and amphibians. We feed the resident ravens who keep hawks away from my chickens. They have their own bowls that we fill with any birds killed by window strikes, trapped mice and rats, cat food and the occasional cracked chicken egg. I’m amazed at how they seem to appear out of nowhere to check out anything new in their bowl. They routinely fly over to investigate the various places we might have left them a treat, a skill that increases their survival and that of their young.

The Guinness Book Of Records has a category for ‘The number of tricks completed by a chicken in one minute’, which I thought was a pretty tall order. Since no one has submitted a claim thus far, the organizers mandated Emily must have at least five tasks correctly completed by one hen and documented by video, photos and witnesses.

For the big day ten people squeezed into her garage which is outfitted as a workshop and doubles as the chickens’ training area. Lacey was chosen as the hen most likely to meet the challenge. Perhaps the crowd inhibited her performance as she was only able to complete eight events, although could easily do more. Her claim has been submitted to the Guinness folks and they’ll have to wait three months to see if they’ve made it in the annals of history.

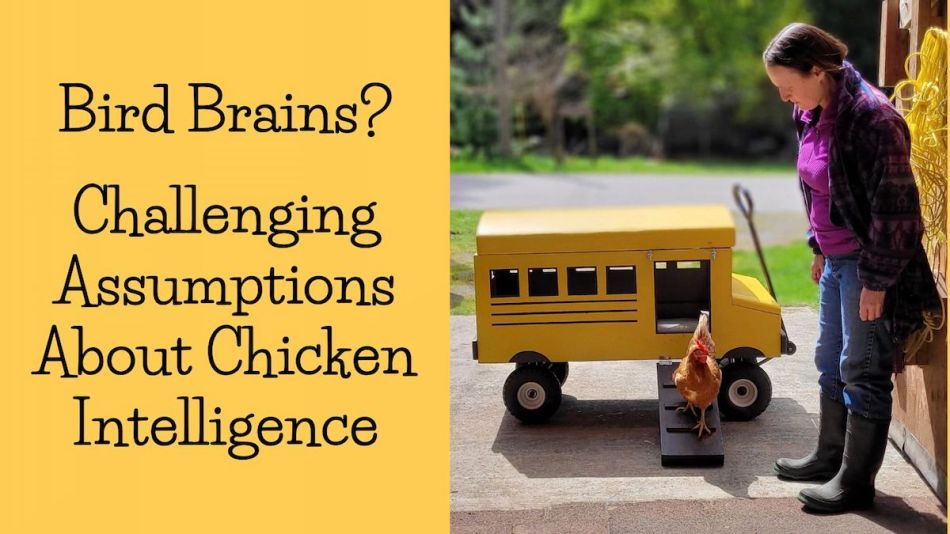

Emily offered to put several birds through their paces to show me some of ‘tricks’ they were required to do for the Guinness challenge. First step was to get the test subjects. She wheeled a school-bus themed wagon, which she built, over to the coop. The flock organize themselves, in preparation for leaving the pen, so they always line up in order. Hen #1 approached the gate and once opened she trotted over to the bus, up the ramp and waited for transport. I was interested to see that the other hens didn’t make a dash for the gate knowing that treats were in store, but waited patiently for their turn.

Once at the garage the hen disembarked and headed for the training area: a large square of poly sheeting taped to the concrete floor marked out in one foot squares. Various props sat on the workbench.

Emily demonstrated some of the tasks her hens have learned and once completed she raised her arms, said, “All done” and the hen turned away from her 180°, vocalized and waited to be picked up. This is a behaviour that all the hens display and was completely initiated by them. Perhaps it’s an instinctual behaviour based on taking direction from the flock’s head hen, acknowledging Emily holds that position. Having birds that allow you to pick them up without a fuss also comes in handy if you’re dealing with a sick bird or need to do a health check.

She brought out two other hens, individually, who performed other tasks. Each one waited at the coop gate, in order, and clearly knew what was expected. All of them are pros, some better than others at particular activities or performing at different speeds. Emily now has her training techniques down pat so her girls learn things within five minutes and perfect them in about a week. She feels once they’ve learned a skill they do retain it, although their performance speed slows to a glacial pace when they are out of practice.

She starts the colour challenges by using a particular coloured shape (i.e. yellow square) on the floor and when the hen pecks at it they get a treat. No peck, no treat. Wrong object, no treat. As you can imagine it doesn’t take long for them to correlate yellow with a treat. Once that behaviour is learned different colours are added and rewards are only given for pecking the yellow object. Just like my dogs, chickens are highly motivated by food. Emily gives them a small amount of scratch or bread to reward them for a task once completed correctly. I asked if their performance is better when they are hungry, but it seems the converse is true: they do work faster, but ultimately make more mistakes.

Learning activities also include recognizing shapes. The hens are trained to peck at particular letters or geometric shapes (either fridge magnets or those printed with black ink on paper) and not others. They can find a specific letter when shown the complete alphabet of 26 letters. Some tasks are easier to learn than others: pecking at the three dots and not one dot results in a 70% success rate for beginners. The letter challenge results in a 90% pass. Similar to an eye chart for people, Emily has made the targets different sizes and discovered that they can become too small for the birds to discern them accurately.

Training is most successful if the objects are placed 5’-6’ away, at least to start. The closer they are the more difficult it is for them to see. Unlike people, each chicken eye is designed for a different function: one for close up (i.e. finding food) and one for distance (i.e. seeing predators). They tend to pick the object on the right 75% of the time if they can’t tell the difference between two objects they are presented them with. It’s clear that they recognize shapes, rather than shadow or light, so the angle at which objects are presented also makes a difference.

Emily is constantly challenging herself and her flock to see how far she can take her training regime. She’s learned a fair bit about their visual and cognitive abilities. She’s unsure whether their response to a particular configuration (i.e. three dots) is because they can determine the number or because more black objects are more dense and therefore easier to identify than just one dot.

“I have to limit the number of things I try in order to assess each thing individually. Maybe if I get another batch of chickens I’ll try with them.”

What kind of things are these hens able to do?

- Peck the disc with three black beads on it and not the one with just one bead

- Peck at the orange fridge magnet A and not S

- Peck at the printed black letter A and not S

- Peck at yellow fridge magnet O and not Z

- Peck at black fridge magnet J and not L

- Peck at purple fridge magnet 5 and not 7

- Peck a yellow card and not the three other coloured cards

- Peck the letter B not H

- Knock over a paper cup to get the treat underneath

- Jump on to a pedestal and then through a hoop to another pedestal

- Pull a string to ring a bell

- Pull a piece of tape to grab a foam ball

- Climb up and down a ramp to ride in their school bus wagon

One of the assignments they failed was to differentiate between the lower case letters ‘d’ and ‘b’ as they are mirrored images.

One of the things I noticed was how calm her birds are. The coop and garage are fairly close to a main road, yet the hens didn’t get spooked by noise, nor by my presence. In contrast, my birds who are under my feet when I’m with them are very cautious with strangers. My previous rooster, at the first sight of potential danger, would lead all the hens into the coop and would stay there until the perceived threat had passed.

It’s evident that Emily isn’t interested in training her birds to do tricks for tricks sake. In exploring the behaviour and cognitive workings of chickens she’s discovered they are cooperative, able to think and make considered choices. In short, they are far more than simple ‘bird brains’.

She’s learned that, although they might not express the emotional range of mammals, they do feel things that are expressed through body language, movements and vocalizations. There are things they like or not, have knowledge of their surroundings, and what they are doing and want. “Once they understand what you want they are cooperative and interactive. I believe they haven’t reached their limits yet.”

Thanks to Dr Emily Carrington for sharing her insights and dedication to furthering our knowledge about how, and what, chickens learn.

If you’re interesting in seeing this flock in action, check out some short videos at my YouTube Bitchin’ Chickens channel and at Emily’s channel The Thinking Chicken. We were both surprised that one of the reels I posted on Facebook reached 1.5 million views in just the first ten days. I was pretty stoked to see that folks are interested to see what chickens can learn and it validates all of their trainer’s confidence and hard work.

Well, now I will have to apologize to everyone I know for my stupid chicken comments…I love my chickens dearly, but I do frequently make comments on their lack of ability to learn and now I stand corrected, and I’m going to have to experiment myself!

LikeLiked by 1 person