If you look at photos depicting the evolution of purebred dogs or cats you’d be impressed to see how much has changed over just a few short decades. They are bred selectively to produce particular traits (i.e. long muzzles in collies; shortened faces in bulldogs; curly or no hair in some cats), some of which can be problematic. The interesting thing about genetics is that often what is visible can be connected to other traits or issues that can remain hidden (e.g. white dogs or cats have higher rates of deafness).

A case in point is the Munchkin gene in cats. I first came across them watching Facebook reels featuring cats with disarmingly short legs. Some folks might find that endearing but my first thought was for the health issues of animals that were deliberately bred to be dwarves.

If you’ve ever seen a chicken with unusually short legs and a low-slung body, then you’ve likely encountered the Creeper gene in action. This gene, fascinating from a genetics perspective and controversial in breeding circles, is a perfect example of how one small mutation can have big effects, both visible and hidden.

The Munchkin gene in cats and Creeper gene in chickens are functionally similar in that both cause shortened limbs due to disrupted bone growth, but they arise from different mutations and genes in each species. The Creeper causes chondrodystrophy (abnormal cartilage development) in chickens, whereas the Munchkin results in disproportionate dwarfism in cats (short limbs, normal body). Both genes share the following traits: short-legged animals with otherwise normal body proportions; dominant visible traits but are lethal in homozygotes (two copies of the gene) and have been selectively maintained in certain breeds for aesthetic reasons.

What Is the Creeper Gene?

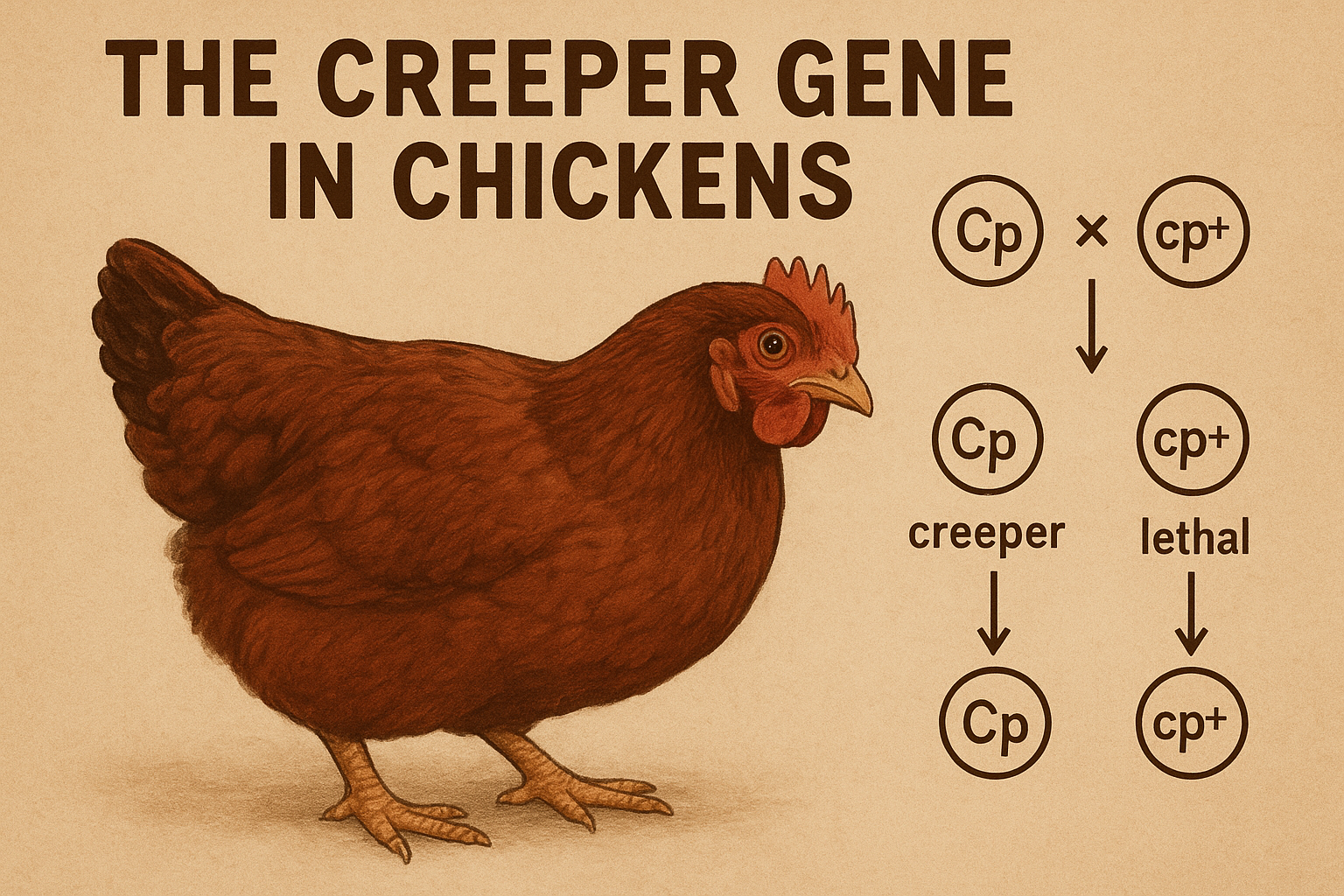

The Creeper gene, symbolized as Cp, is a dominant lethal gene first documented in chickens over a century ago. It causes chondrodystrophy, a form of dwarfism resulting from abnormal cartilage development.

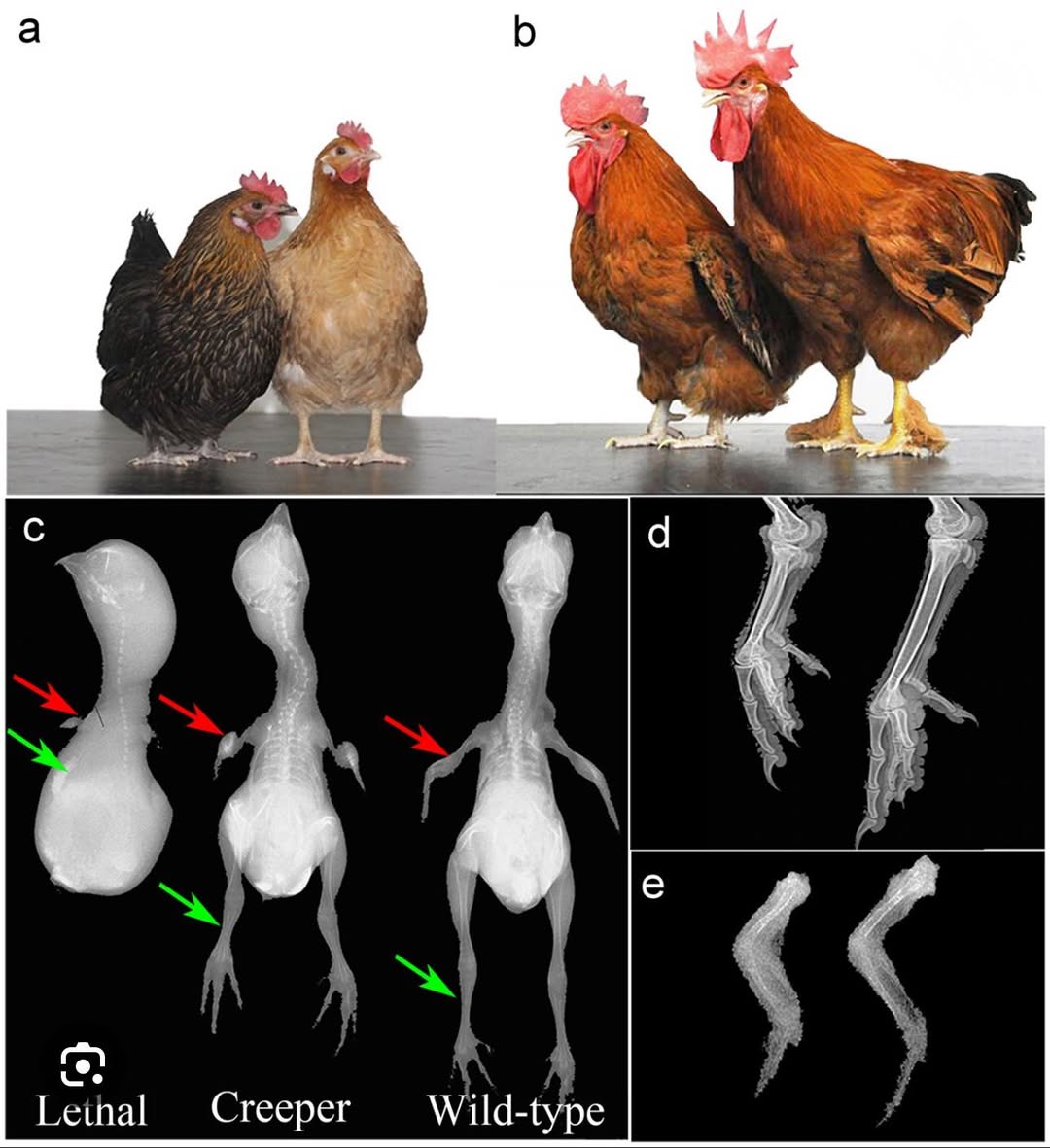

- Chickens that inherit one copy of the gene (Cp/cp+) display the characteristic shortened legs and compressed body structure known as the Creeper phenotype.

- Chicks that inherit two copies (Cp/Cp) do not survive embryonic development and die before hatching.

- Birds without the gene (cp+/cp+) are normal-legged and typically indistinguishable from standard breeds.

This means every Creeper chicken, by definition, carries one normal allele and one creeper allele and about 25% of embryos from two creeper parents will not hatch due to the lethal combination.

The Creeper gene affects endochondral bone growth, which is the process responsible for lengthening the legs, ribs, and certain facial bones. In Creeper chickens, cartilage cells stop dividing earlier than usual, leading to shortened bones and sometimes a widened skull base.

- The gene is autosomal, not linked to sex chromosomes.

- It’s dominant for the short-leg trait but recessive lethal, meaning the lethal outcome only appears when two copies are present.

- This makes breeding Creeper-to-Creeper risky, as roughly one in four embryos will fail to develop.

Breeds That Carry the Creeper Gene

Several heritage and ornamental breeds have been historically associated with the creeper gene, including:

- Chabo (Japanese Bantam): the most well-known Creeper-carrying breed, known for its extremely short legs and upright tail carriage.

- Scots Dumpy: A rare breed from Scotland characterized by a waddling gait and low body stance.

- Indian Game (Cornish): Some lines have been observed with Creeper-like phenotypes, though not all carry the gene.

In these breeds, careful selection has kept the gene in the population for aesthetic reasons, but it also means breeders must be mindful of pairing.

Japanese Bantams (Cackle Hatchery) and Scots Dumpy (Unknown)

Ethical and Practical Considerations

While the Creeper gene gives certain breeds their iconic look, it comes with clear ethical challenges:

- Embryonic lethality reduces hatch rates and can raise animal welfare concerns.

- Mobility issues in adult birds may occur, depending on severity of leg shortening.

- Managed matings pairing creeper to normal-legged birds to avoid lethal combinations.

For these reasons, most breeders maintain genetic diversity and emphasize health over appearance. In research contexts, the Creeper gene continues to be studied as a model for bone growth disorders in other species, including humans.

Like many quirks of chicken genetics, the Creeper gene reminds us that beauty often comes with biological complexity. The striking stance of a Chabo or Scots Dumpy may be charming, but understanding the genetics behind it – and breeding responsibly – is crucial to ensuring the welfare of future flocks.

Citations

- Dunn, L. C. (1928). Lethal factors in domestic fowl. Genetics, 13(2), 115–151.

- Landauer, W. (1941). The Creeper fowl: A study of an incomplete dominant lethal mutant. Genetics, 26(1), 1–23.

- Hutt, F. B. (1949). Genetics of the Fowl. McGraw-Hill Book Company.

- Somes, R. G. (1988). International Registry of Poultry Genetic Stocks. Storrs Agricultural Experiment Station, University of Connecticut.

- Somes, R. G. (1990). Mutations and major variants of plumage and skin in chickens. In Poultry Breeding and Genetics (pp. 169–208). Elsevier.

“Serious science. Not-so-serious chickens.”

You really do an excellent job of explaining complicated things. Thank you. m

LikeLike

Thanks for the feedback. I love to teach and am glad my work is helpful.

LikeLike