If you own a dog or cat it’s par for the course that you will spend some significant time and money taking your pet to a vet: spaying/neutering, vaccinations, or for illnesses and injuries. My Standard Poodle, Simon, cost me a small fortune in his ten years and I would joke with my vet that I subsidized his kids’ college fund. Most of us are prepared to take a dog or cat for medical help even if it does strain our budget because of social expectations of pet stewardship or, more importantly, that we have come to see those animals as members of our family. To deprive them of care would be deemed irresponsible.

Poultry, on the other hand, are a different matter. They are usually seen to be either as livestock or pets. Some farmers might define their value strictly in terms of meat or egg production and wouldn’t bother spending money on vet care for an animal that can easily be replaced for far less. But as more folks get backyard chickens I see that those keepers increasingly seeking out medical advice, often on Facebook chicken groups.

The internet can be a wonderful resource where we can connect with like-minded or more experienced folks that can advise as with various aspects of chicken care. Some of those more common issues are relatively easy to diagnose and suggest a course of action or treatment. The downside is the internet is democratic; meaning anyone can join a group or give advice regardless of their training. In my experience some of those folks don’t understand their limitations and often perpetuate erroneous advice. You know the school of “I’ve always done it this way and never had a problem”.

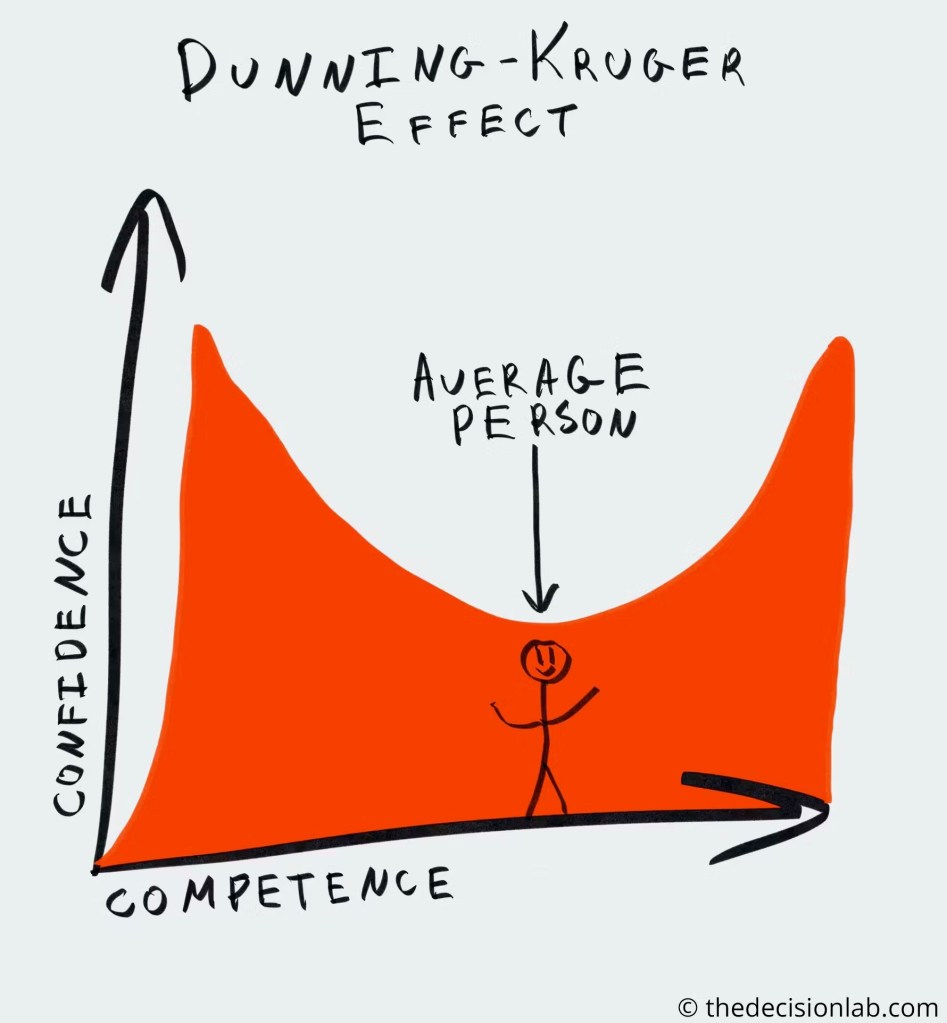

I came across the idea of the Dunning-Kruger effect and think it’s so fitting to describe online groups.

“The Dunning-Kruger effect is when a person does not have skills or ability in a specific area but sees themselves as fully equipped to give opinions or carry out tasks in that field, even though objective measures or people around them may disagree. They are unaware that they do not have the necessary capabilities.” – Wikipedia

In short, most folks know less than they think they know on a given subject. However, that doesn’t stop them from weighing in and potentially giving out the wrong information.

One contentious issue is whether to take a chicken to a vet or not? Some say, “Why bother for an animal with a short life expectancy or whose monetary worth isn’t much. Chicks can be found at big feed stores for under a dollar.” Others are in a quandary because of their location, budget, lack of access to a vet or even finding a vet with any avian experience.

I’ve been really fortunate to have found a mentor to guide me along, to bounce those questions off, to explain why or when it’s important to seek veterinary help. And sometimes when to admit your bird is beyond help and to humanely euthanize it.

I’ve been getting together with Dr Vicki Bowes over the last three years to do necropsies of my birds, fecal float testing and to pore over posts that I’ve found, or been sent, about chicken health issues. We’ve turned those into a couple of series: more than 450 pathology case studies, and another about refuting online myths.

Dr Bowes is not only a DVM (Doctor of Veterinary Medicine), but also holds a Masters degree in Avian Pathology. All DVMs are trained in small animal (i.e. mammal) medicine. Some get further training in large livestock or exotics. Most have had very little exposure to avian anatomy, physiology or pathology, yet alone experience in treating poultry.

Both Dr Bowes and I appreciate when a small animal vet is willing to see chicken patients but often their training is inadequate. It’s important to get professional help but make sure your vet actually has some experience with poultry.

Photo credits: Abriana Humphress and Danyelle Brown

You need to get an accurate diagnosis and treatment plan from a trained professional, not advice from someone on Facebook who’s trying to be helpful but is giving you so many contradictory suggestions. Dr Bowes would have a fit reading some of what is being suggested by folks that haven’t seen your bird and don’t know for sure what’s going on.

This is one of the reasons that veterinary medications have been restricted. Before you get all the things online posters recommend, understand what they are used for and the contraindications. Sometimes throwing everything but the kitchen sink at a vulnerable bird can make things worse.

Here are some guidelines for when your bird needs veterinary care:

- If the condition is life threatening (i.e. compound fractures, torn or missing wings or legs, serious predator attacks with large areas of missing skin or exposed muscle).

- Significant blood loss or unstoppable bleeding.

- Don’t evaluate injuries solely on open wounds or bleeding. Some predators, especially dogs, can cause crushing injuries and internal damage that is not visible to the eye.

- Longstanding bumblefoot infection. Both Dr Bowes and I don’t recommend at-home ‘surgery’; cutting into the foot can damage tendons, nerves and blood vessels. There are safer options (i.e. soaking and using a drawing salve). If the infection is persistent or deep, antibiotics may be required.

- Any condition that requires an antibiotic. In both the USA and Canada they are obtained only through a veterinary prescription. It’s important to understand that antibiotics should be used to target bacterial, and not viral, infections. There are different drugs that are used to effectively treat different areas of the body or different kinds of pathogens. Antibiotics are not all the same and are often not interchangeable.

- Most respiratory infections, because they often require an antibiotic.

- Any issue that requires pain management. As prey animals, chickens have evolved to hide their pain but that doesn’t mean they don’t experience significant pain as a result of illness, injury or predator attacks. Most backyard chicken keepers use off label drugs. Meloxicam is the pain medication most recommended for poultry.

- Conditions that require anesthetic or surgical interventions such as amputations, crop surgery or stitches.

- Veterinarians prescribe drugs approved for specific indications according to labeled recommendations and withdrawal periods. If off label drug use is indicated by a veterinarian’s prescription, they have to establish and document appropriate withdrawal periods. Understand that some medications may be approved for use in poultry in some jurisdictions, but not others.

Dr Bowes suggests that you apply some empathy when dealing with your sick or injured bird. Ask yourself, “If this were me/my child with this condition would I seek medical intervention? Go to the hospital?” If the answer is yes, then your chicken probably requires a vet, hopefully one with avian experience.

If your only option is at home care you’ll need to do the following:

- Assemble a good first aid kit

- Set up a sick bay in a warm, quiet place

- Treat for shock and pain, if applicable

- Keep your bird hydrated. Water is more important than food in the early stages of recovery

- Treat wounds, splint fractures, repair beak injuries, watch for signs of infection

- Monitor and record progress, symptoms, indication of improvement during the first 48 hours

- If there is no significant improvement by 72 hours then consider humane euthanasia

Thanks to Dr Bowes for her on-going mentorship and input on this post.

Comprehensive and wise. m

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for the feedback

LikeLike

Since joining FB recently, I have seen this very thing in several chicken groups. I feel like most of the time, people are genuinely trying to help someone help their chicken, but the amount of conflicting advice makes my head swim.

Then people start arguing about what is right and what’s wrong…. ugh. It’s too much.

I hate that vet care for chickens isn’t readily available for a lot of us. We’ve all just got to do the best we can and online research is a part of that. I’ve recommended your site to several people now. I hope they’ve come by to check it out. – Alicia

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for the feedback and sharing my site.

LikeLike