I don’t know how many times I’ve heard someone say “chickens don’t feel pain like we do?” Really? How do they know that? I’m assuming they’ve drawn that conclusion because birds, unlike mammals, aren’t usually vocal when suffering pain. If you think about it, chickens are prey animals and when they’re sick or incapacitated they’re targets for predators looking for an easy meal. If you’ve ever observed your flock you can usually figure out who’s not doing well, not because they’re screaming, but due to the reverse: they’re more quiet, less active or isolating from the flock.

The common misperception that chickens don’t experience pain in ways recognizable to us has an impact on how we treat them: dealing with injuries without pain meds; performing at-home surgery without anesthetic; removing combs (dubbing), testicles (caponizing) or spurs from roosters; not protecting them from extreme temperatures. I’m sometimes dismayed at the cavalier manner in which chickens are treated. Folks routinely think it’s no big deal when their chicken’s comb or toes fall off due to frostbite. If it were their fingers or toes I guarantee they’d feel pain.

I think most of us do want to mitigate suffering in our birds and are unsure what pain management is appropriate. I hear lots on Facebook chicken groups advising not to use Poly- or Neosporin designed to deal with pain because it’s toxic for birds. Or to withhold pain medications because the dosing is tricky and it’s possible to overdose them with adverse effects.

I decided to do a bit of reading about how chickens experience pain and how, as small flock keepers, we can deal with it.

What Is Pain?

Pain is defined as “a localized or generalized unpleasant bodily sensation or complex of sensations that cause mild to severe physical discomfort and emotional distress and typically results from bodily disorder (such as injury or disease)”. – Merriam Webster Dictionary

There are four categories:

- Nociceptive Pain: result of tissue damage (i.e. cuts, burns)

- Inflammatory Pain: inappropriate response by the body’s immune system

- Neuropathic Pain: nerve irritation

- Functional Pain: without obvious origin

How Chickens (& People) Perceive Pain

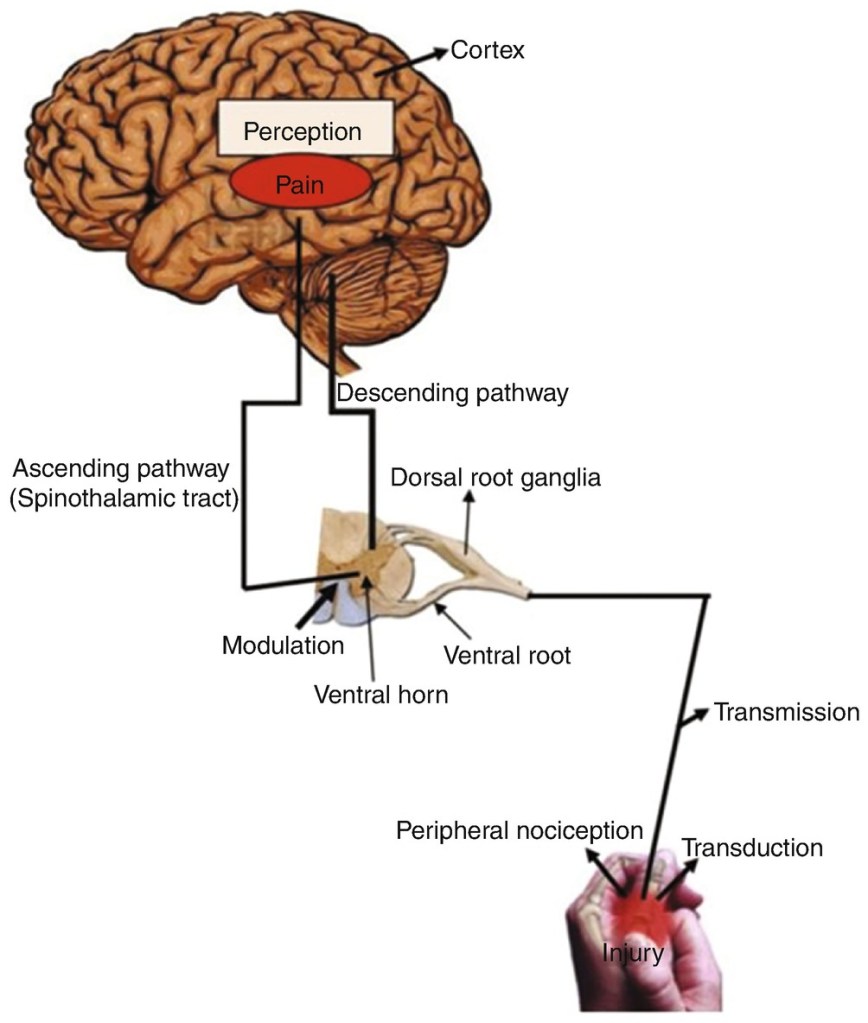

The Nervous System is made up of the brain and the spinal cord, which combine to form the central nervous system; while the sensory and motor nerves form the peripheral nervous system. Think of the brain and spinal cord as hubs, while the nerves are information pathways that stretch out all over the body.

Sensory nerves send impulses about what is happening in our environment to the brain via the spinal cord. The brain then sends that information back to the motor nerves, which help us perform actions. It’s a complex system that is communicating information 24/7 directing the body’s responses.

The recognition of pain involves both detection at the site and responses to the information it receives on special pain receptors on the brain, called nociceptors. They are activated whenever there has been an injury, or even a potential injury, such as breaking the skin or causing a large indentation. If you hit your thumb with a hammer sensory nerves react to produce chemicals, which determine how those sensations are interpreted.

In birds the thermal nociceptors are less sensitive to cold compared to mammals, while their threshold for heat tends to be higher. When tissue damage occurs it results in a drop in pH and the release of inflammatory mediators, signaling the nocireceptors to respond.

Pain is signaled in both birds and mammals in similar ways: the central nervous system (CNS) processes all information relating to potential injury or damage. This supports the hypothesis that birds are capable of perceiving pain similar to mammals.

Prey animals, in order to survive, modify their responses. Birds typically indicate pain by isolating from the flock, lethargy, ruffled feathers, hunched, roosting on the coop floor or in a nest box, decreased appetite, constipation, abnormal gait, closed eyes, lameness or biting at wounds.

Treating Pain In Chickens

There are three general classes of pain medication used in avian veterinary medicine: Opioids, Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs), and local anesthetics.

Opioids

Many of you are aware of the ‘opioid crisis’ that various places in the world have been struggling with over the past several years. Opioids are effective for alleviating pain, but they must be used with care as the most common side effect is cardiac and/or respiratory depression, which can lead to death. The use of opioids in veterinary medicine is not widespread and not enough research has been done to suggest their efficacy in birds.

Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs)

Aspirin (Acetylsalicylic Acid) is the most common NSAID used for people to treat pain, fever and inflammation. Studies in birds have shown varied effects related to both body weight and species of bird, so more research is needed to determine proper dosage for each species.

If you do require over-the-counter pain meds: the recommended dosage is ½ tablet of baby aspirin (81mg) for an adult standard sized bird. Aspirin can be diluted in drinking water or given orally. Only use if there is no chance of internal bleeding or wounds with active bleeding, because aspirin acts as a blood thinner and inhibits clotting.

Meloxicam (Metacam) is commonly used in mammals and is the most recommended medication to treat acute or chronic pain and inflammation in chickens. Studies of its half-life (a measure of the time it takes to wear off) is inversely proportionate to the bird’s weight (i.e. smaller birds need less than larger birds, which also may require increased dosing intervals). For example, ostriches exhibited a very rapid half-life when compared to chickens. Dosage: .1-2mg/kg.

Rimadyl (Carprofen) is an oral or injectable anti-inflammatory used ‘off-label’ for minor or chronic pain relief in chickens. Caution: It can interact negatively with aspirin.

NSAIDs are excreted through the kidneys, so overdosing can lead to kidney damage.

Local Anesthetics: block channels that prevent pain impulses. Birds may be more sensitive to the toxic effects of local anesthetics than mammals which are related to the balance between absorption and elimination. Toxic effects (i.e. seizures, cardiac arrest, depression, gait issues, and involuntary, rapid eye movements) have been documented in birds at proportionately lower dosage than in dogs.

Lidocaine is used in birds, however appropriate dosing may be difficult. It should be diluted 1:10, with total dosage not exceeding 4 mg/kg.

Benzocaine has been used topically for local analgesia for minor wound repair.

Natural Remedies

Two homeopathic remedies, readily purchased in health food stores, can be used for chickens: Arnica Montana for bruising, injury, and shock; and Aconite for shock. It comes in a tiny pellet form which can be added to their drinking water, food or given orally. One or two 30x pellets should be sufficient.

CBD: is a non-intoxicating oil made by extracting CBD from cannabis, then diluting it with carrier oil like coconut or hemp seed oil. As the demand for alternative pharmaceutical products increases for people so, too, does it for our pets.

Products for animals are available in some of the same forms as people, including edibles (chewable treats and capsules), oils that can be added to food or placed under the tongue, and topical creams or balms that are massaged directly on the skin.

Traumeel: is a natural remedy containing 12 botanicals, taken orally or topically for the treatment of inflammation, muscle and joint pain.

A Note On Pain: “As a Vet with the Masters degree in Animal Welfare, and a lot of experience developing euthanasia programs, my philosophy is this: when an animal is sick, indicating tissue failure, there will be discomfort and pain. Chickens are incredibly stoic and hide pain better than just about any other animal. If you allow the tissue to fail to the point of death, you have allowed the maximum amount of suffering that animal can go through. The moment you’re convinced that the animal has a low chance of recovery, that is the maximum amount of suffering you can avoid.

Everyone will make that hard decision at a different point, but once it’s made, the suffering beyond that is unnecessary, and can be spared by euthanasia. Are there miracle recoveries? Yes. But if you wait and hope for the miracle recovery, the 99% that don’t, will suffer the maximum amount they can, and I feel that that is not doing a service to the birds in your care. I recommend everyone learn how to euthanize, or commit to taking their bird to a vet to be euthanized when the time comes.” – Dr Mike Petrik, DVM

Credits: Dr Michelle Hawkins, DVM UC- Davis; Dr Mike Petrik, DVM; Poultry DVM; Very Well Health. Featured Photo: salon.com

Thank you for writing on this topic. I’ve never understood why humans insist that ‘animals’ (broadly speaking) don’t suffer pain. Perhaps we need that defense to let us off the hook of responsibility for the harms we cause or are witness to.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Well said and well researched. There is not much (accurate) information out there on treating chicken pain and the need for anesthesia for painful procedures. Thank you for that. As an aside, you might want to mention the FARAD (Federal Food Animal Residues) program regarding off-label drug use since there are very few medications actually licensed for use in chickens and some are illegal in chickens because they are legally considered food animals (even if they are just pets or no longer laying eggs). I look forward to reading the rest of your blogs! Aloha, Keri Jones, DVM, CVPP (Certified Veterinary Pain Practitioner and pet chicken owner)

LikeLiked by 1 person

I believe you meant “directly proportionate to weight,” in terms of dosage since a smaller bird needs less. If the smaller the bird got and it needed more, then it would be an inverse relationship for dosage, but it is an inverse relationship in terms of time it takes to wear off..ie half life. It was just slightly confusing because it wasn’t quite clear whether it was half life or dosage amount that had the inverse relationship..

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for pointing that out – I’ll edit the post for clarity.

LikeLike

Thank you for writing on this important topic. I’ve searched the web and have even asked local Veterinarians for information on treating pain in chickens and haven’t found much helpful information. I’ve had to wing it (pun intended!) on my own when it comes to treating my micro-flock. This article is the most comprehensive information I’ve seen yet, particularly regarding using CBD in chickens. Please continue educating us on this vital subject.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I really appreciate this. I am fortunate to have a vet who can do poultry close by and she’ll see birds I need to bring in, but also give me advice and prescribe with info from emails and photos I send. Meloxicam has definitely been useful in a couple of foot problems as well as a raccoon bite incident. It is expensive stuff, but if I can make their lives more comfortable it is well worth both the price and the egg withdrawal times (although I’ve treated more roosters than egg layers, actually!)

We have lots of CBD options around since it’s all legalized in my state. I’ll have to look into that and see if it would help when my guys are having issues.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You’re very fortunate to have access to a vet who treats chickens. Most small animal vets are only trained to deal with mammals, so even if they are willing, they lack expertise with avian species.

LikeLike

So glad to read this piece! Thank you for sharing. I am curious about signs of pain in chickens, besides the obvious. As Dr. Petrik points out in your article, chickens are experts at hiding pain. I’m wondering about some of the more subtle signs, such as closing eyes, quietly fluffing up, and perhaps vibrating. Not the vibrating contented purr or trill, but something more like an intermittent shiver. Wondering if you or anyone else has observed this potential indicator?

LikeLike