If you’ve ever corresponded with me via email you’ll know that my handle is skullgrrrl. That moniker is the result of a decades long interest in collecting animal skulls. At one point, my collection consisted of 350 species from around the world. Of course, I had a chicken skull.

I’ve written about different anatomical systems in chickens – digestive, nervous, immune and respiratory – and thought I’d write a bit about poultry bones. Since chickens are the most populous avian species in the world and people have eaten them we’re all probably familiar with at least some of those bones.

Osteology, the study of bones, can provide insight into the anatomy, physiology, and evolutionary biology of animals. In chickens, it’s significant for veterinary science, poultry farming, archaeology and comparative anatomy. The chicken skeleton is a unique combination of lightness and strength, uniquely adapted for a life of limited flight, high reproductive output, and ground foraging.

Chickens, like all birds, have a skeleton that balances the need for mobility with the demands of egg production and body support. One interesting fact about chicken bones is that they are much lighter than those of other birds. This allows chickens to have a higher ratio of muscle to bone, making them more efficient at moving around.

The examination of chicken bones reveal the legacy of avian evolution with adaptations for survival, reproduction, and domestication.

Skeletal characteristics include:

- Lightweight, pneumatic bones: Some bones are hollow and contain air sacs that connect to the respiratory system, reducing body weight.

- Fused bones: To provide stability for locomotion and wing use, many bones are fused.

- Bone rigidity: Birds lack intervertebral discs in most of the spine, making their vertebral column stiff, which is useful for balance and strength.

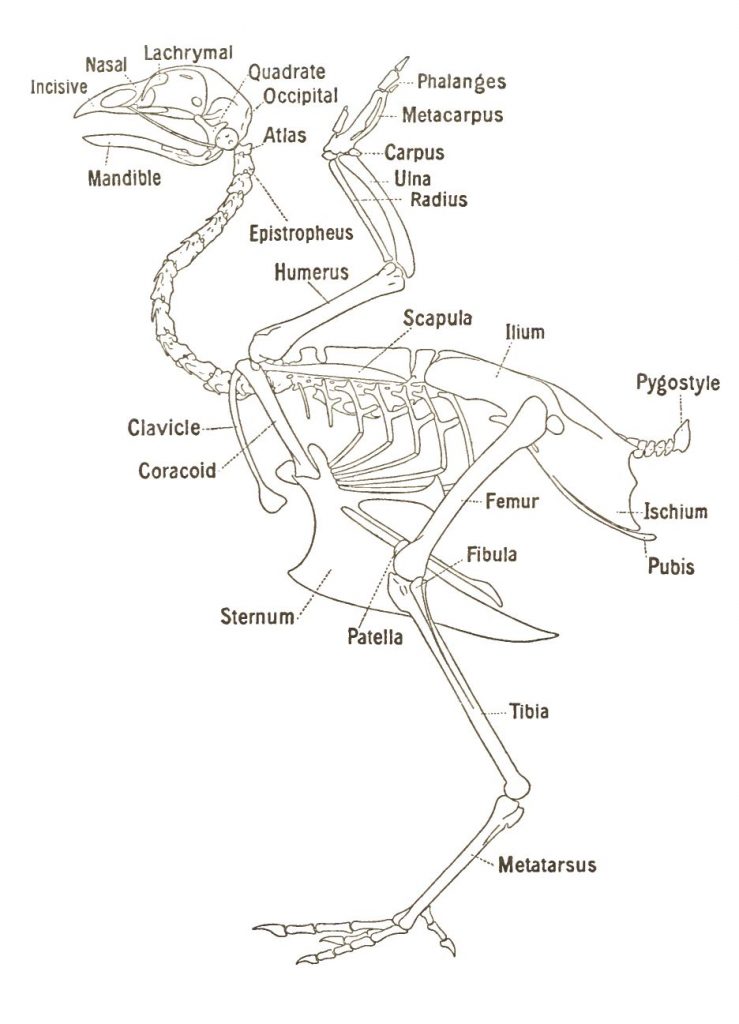

Parts Of The Skeleton

- Skull: Relatively lightweight with large eye sockets and a beak in place of teeth. The skull is fused, providing protection and rigidity.

Vertebral Column

- Cervical (neck) vertebrae: Chickens have 14 cervical vertebrae, allowing a wide range of motion in the neck.

- Thoracic vertebrae: Typically seven, many of which are fused for added support.

- Synsacrum: Fused lumbar, sacral, and some caudal vertebrae, which support the pelvis.

- Pygostyle (Pope’s nose): A fusion of the last caudal vertebrae, supporting tail feathers.

- Ribs: Usually seven pairs, with bony extensions that overlap for added strength.

Pectoral (shoulder) Girdle

- Clavicles: Fused to form the furcula (wishbone), which acts like a spring during wing flapping.

- Scapula: A long, thin bone supporting wing movement.

- Coracoid: A thick bone that helps brace the wing against the sternum.

Wings

- Humerus, radius, ulna: The equivalent of the upper arm and forearm in humans.

- Carpometacarpus: Fusion of wrist and knuckles.

- Phalanges (toes): Reduced digits adapted for feather attachment.

Pelvic Girdle

- Composed of the ilium, ischium, and pubis, fused to the synsacrum.

Legs

- Femur: Thigh bone.

- Tibiotarsus: Fusion of tibia and some tarsal bones.

- Fibula: unique bone structure in chicken legs which runs parallel to the tibia (shin bone) and helps to support their weight.

- and splint-like: Fusion of lower leg and foot bones.

- Phalanges: Typically four, although some breeds have five, toes with three facing forward and one (the hallux) backward.

Image credit: Unknown; Poultry Hub Australia

Special Adaptations

- Keel: A large, sharp extension of the sternum that anchor the flight muscles. The keel is much larger in chickens than in other birds and gives them their characteristic pear-shaped appearance. Though chickens are poor fliers, this structure remains prominent. When birds are ill and underweight the keel becomes more obvious.

- Medullary Bone: In hens, this temporary bone forms inside long bones as a calcium reservoir for eggshell production during laying.

- Beak: The beak lacks teeth and is lightweight, and the upper beak can move slightly thanks to specialized joints, a feature known as cranial kinesis.

Development and Growth

Chickens hatch with a skeleton made of cartilage that becomes bone as they grow. Plates at the ends of long bones allow for rapid growth, especially in meat breeds like broilers. Skeletal deformities such as bowed legs or slipped tendon can occur due to genetic issues or nutritional imbalances.

Understanding chicken osteology assists with:

- Diagnosing skeletal disorders (e.g., rickets, fractures).

- Evaluating welfare: Bone strength and integrity are indicators of health, especially in fast-growing breeds.

- Breeding programs: Selective breeding can impact skeletal structure, requiring knowledge of anatomy.

Click here for a post on skeletal deformities

Thank you for this most informative post about avian bones with aa emphasis on the differences between general avian and chicken bones ! This not only informs my chicken keeping practice but also my drawing/ art practice !

LikeLike